Relation of Pleistocene to Prehistoric Period.—Magnitude of the Interval.—Animals.—Physical changes.—Excavation and filling up of Valleys: Fisherton; Freshford.—Comparison of Deposits in Valleys with those of Caves.—Differences of Mineral Condition.—The Pleistocene Caves of Germany: Gailenreuth; Kühloch.—Of Great Britain.—The Caves of Yorkshire: Kirkdale.—Of Derbyshire: The Dream Cave.—Of North Wales, near St. Asaph.—Of South Wales, in counties of Glamorgan, Caermarthen, Pembroke.—Of Monmouth.—Of Gloucestershire.—Of Somersetshire: Uphill, Banwell, Bleadon, Sandford Hill, Wookey Hole.—The District of Mendip higher in Pleistocene age than now.—The condition of bones gnawed by Hy?nas.—The Caves of Devonshire: Oreston; Brixham; Kent’s Hole.—The probable age of the Machairodus of Kent’s Hole.—Those of Ireland, Shandon.

Relation of Pleistocene to Prehistoric Period.

We have seen, in the fifth and sixth chapters, that the caves offer valuable information as to the prehistoric ethnology of Europe, and that they prove the ancient neolithic population to stand directly related to the Basque and Celtic elements in the present inhabitants of Britain, France, and Spain. We shall discover in the course of this and the following chapters that no such265 continuity can be made out between the pal?olithic man of the pleistocene age and any of the races now living in our quarter of the world; and we shall see that he is separated from his neolithic successor by an interval of time, the length of which cannot be measured in terms of years. Before the pleistocene group of caves be examined, it will be necessary to define the relation that exists between the prehistoric and the pleistocene periods.

The Animals—Magnitude of Interval.

The prehistoric mammalia consist, as we have seen (p. 136), with the solitary exception of the Irish elk, of the wild animals at present living in Europe, together with the domestic species and varieties introduced by man, probably from central Asia. In the rest of this work we shall have to deal, not merely with the wild animals at present inhabiting Europe, but also with those which have either become extinct, or have migrated to Asia, America, or Africa. Besides this addition to the European fauna in the pleistocene age, the total absence of the domestic animals is a most important feature. The dog, goat, sheep, Celtic short-horn, and domestic swine are conspicuous by their absence: the reputed association of their remains with those of the pleistocene mammals being due, in all the cases which I have examined in France and Britain, to a confusion between distinct strata in the same cave or river-deposit, which are respectively of pleistocene and prehistoric or historic ages. Thus in the excavations in the gravel underneath London, the Celtic short-horn and goat of the superficial strata are very generally mixed with the266 reindeer and mammoth of the pleistocene gravels below, by the collectors, and the names of the domestic animals have crept into the pleistocene lists. None of the domestic animals have been recorded from any carefully explored strata of that age in any part of Europe.

The following late pleistocene species were unknown in Britain in the prehistoric age:—

Glutton.

Spotted hy?na.

Panther.

Lion.

Lynx.

Felis Caffer.

Musk-sheep.

Bison.

Hippopotamus.

Lemming.

Pouched marmot.

Tailless hare.

Lepus diluvianus.

Arvicola Gulielmi.

Cave-bear.

Rhinoceros hemit?chus.

R. tichorhinus.

Elephas antiquus.

Mammoth.

The glutton, lynx, bison, and lemming, still live in Europe, the spotted hy?na, Felis Caffer, and hippopotamus are peculiar to Africa, the lion to Africa and Asia, and the last seven species are extinct. The Machairodus cultridens and Rhinoceros megarhinus probably disappeared in an early stage of the pleistocene. It may reasonably be inferred, from the migration and extinction of so many species between the close of the pleistocene and beginning of the historic period, that the interval was of considerable length; for it would be impossible for such changes to have taken place in a short time.

The same sharp line of demarcation exists between the two faunas on the continent. The panther, Felis Caffer, lynx, spotted hy?na, musk-sheep, hippopotamus, and the extinct group disappeared. The African elephant forsook Spain and Sicily, the striped hy?na the south of France, before the prehistoric period; while the Elephas meridionalis and pigmy hippopotamus of Sicily, and267 the pigmy elephant and gigantic dormouse of Malta, became extinct. Speaking in general terms, the wild fauna of Europe, as we have it now, dates from the beginning of the prehistoric age, and consists merely of those animals which were able to survive the changes by which their pleistocene congeners were banished or destroyed. The arrival of the domestic animals under the care of man in the neolithic age, and their extension over the whole of Europe in a wild or semi-wild state, coupled with the disappearance of the wild species mentioned above, constitutes a change in the mammal life at least as important as any of those which define the meiocene from the pleiocene, or the pleiocene from the pleistocene periods.

Physical changes—The excavation and filling up of Valleys.

The magnitude of the interval between the two periods may also be gathered from the great changes which have taken place in physical geography. In nearly every valley in Great Britain, certain areas to be mentioned presently excepted, are strata of sand and gravel, proved to be of pleistocene age by their fossil mammals, and by their fluviatile shells to have been deposited by rivers. They occur at various heights, forming sometimes terraces, and at others isolated patches, which were accumulated when the river flowed at their level, and before the valleys were cut down to their present depth. Those at Fisherton near Salisbury, described by Sir Charles Lyell, Mr. Prestwich, Mr. John Evans,175 and others, may be taken as an example.

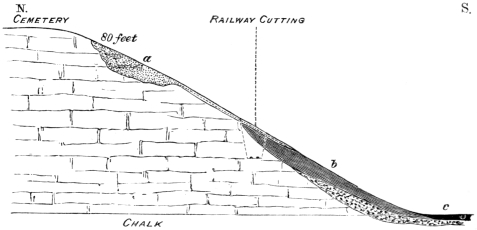

Fig. 74.—Section of Valley-gravels at Fisherton. (Evans.)

The valley through which the river Wily flows is excavated in the chalk (Fig. 74), and on its northern side fluviatile deposits occur at two levels, represented in the accompanying section. One patch of gravel, about twelve feet thick, a, lies about eighty feet above the present level of the Wily; while a second, b, consisting of clayey brickearth or loam, with seams of gravel, and fluviatile shells, sweeps down from a lower point to the bottom of the valley, and passes under the river. From the deposit a, Dr. Blackmore obtained many rudely-chipped implements, of the same pal?olithic type as those found with the extinct mammalia in the gravel beds at Amiens and Abbeville in the valley of the Somme. In the deposit b, fossil mammalia were met with belonging to the following animals:—

Spotted hy?na.

Lion.

Reindeer.

Stag.

Bison.

Urus.

Musk-sheep.

Wild boar.

Horse.

Woolly rhinoceros.

Mammoth.

Lemming.

Pouched marmot.

Hare.

269 Dr. Blackmore subsequently discovered a flint implement along with these animals, of the same type as those previously met with in the deposit a.

A horizontal stretch of alluvium, c, deposited by the floods, occupies the present bottom of the valley. In this section it is plain that the gravels and brickearth at a and b were deposited by a river, which formerly flowed at those levels. In other words, the valley of the Wily was excavated during the time that the pleistocene strata a and b were being formed, while pal?olithic man and the extinct animals were living in the neighbourhood. The position also of b below the present bottom of the valley proves that the latter then was deeper than it is now. The prehistoric alluvium, c, represents the last stage in the history of the valley in which it is beginning to be filled with the deposits of floods. While it was being accumulated none of the animals of a and b were living in the district except the hare, urus, stag, horse, and wild boar.

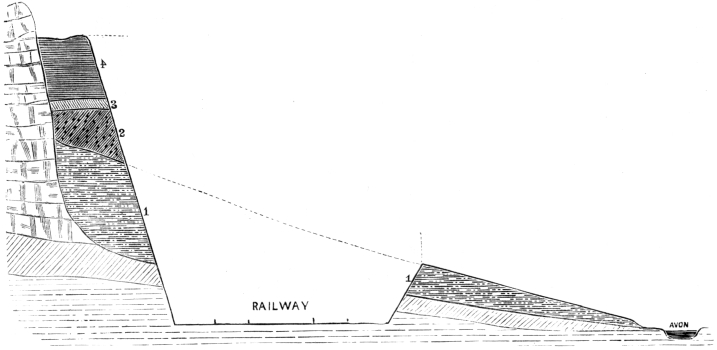

A somewhat similar section is exposed in the valley of the Avon at Freshford, near Bath, in a railway cutting, at a height of about thirty-five feet above the river. A thick mass of gravel abuts directly against a cleft of inferior oolite (Fig. 75), and gradually dies down to the alluvium. In it Mr. Charles Moore discovered the remains of the musk-sheep, and the Rev. H. H. Winwood those of the mammoth, bison, horse, and reindeer. In this case the pleistocene strata occupied the side of one of the valleys which had been deepened since the time of their deposit.

Fig. 75.—Section of Valley-gravels at Freshford, Bath.

4, Red loam, 5ft. 6in.; 3, Oolitic wash, 1ft.; 2, Clay with flints, 4ft. 10in.; 1, Gravel with fossil mammals, 8ft.

The alluvium in the neighbourhood of Bath contains in its lower portion a layer of peat, with bones of the Celtic short-horn (Bos longifrons), stag, roe, horse, goat, and pig; and in its upper part are old refuse heaps,270 proved to be Roman by the coins and ware, which are also met with at various points underneath the surface soil, and sometimes at considerable depths. It is, therefore, of prehistoric and historic age, and since271 it is found only in the valley bottoms, we may conclude that the present courses of the rivers along the sides of which it is found date back from the prehistoric age; while their ancient courses are marked by the fluviatile deposits with the extinct mammalia standing at various levels, the higher being the older. In the section at Fisherton we have evidence that the river flowed at a lower level in the pleistocene age than in the prehistoric, and in that at Freshford that the lower portion of the valley had been excavated after the pleistocene strata had been formed. One or other of these physical changes is to be traced in nearly all river valleys.176 We may conclude that both imply a considerable lapse of time, because similar changes are now produced with extreme slowness. In the pleistocene river deposits, which lie scattered about at various heights on the valley sides, we seek in vain for neolithic implements, or domestic animals. In the low-lying alluvia, and accumulations of peat, we seek equally in vain for traces of pal?olithic man, or of the extinct mammalia, except the Irish elk.

We may also gather, from the localization of the prehistoric alluvia close to the present streams, that the time represented by its accumulation is insignificant in comparison with the long lapse of ages implied by the pleistocene gravels and brickearths, that were deposited at various heights during the excavation of the valleys. The general surface of the valleys has undergone but little change since history began, and the excavation by the rivers has been so small as to have escaped accurate measurement. The alluvia represent272 the principal work done since the close of the pleistocene period.

The most important testimony that the interval between the two periods was very long, is offered by the climatal change, and the severance of Britain from the continent. The arctic severity of the pleistocene winter in these latitudes had passed away before the prehistoric age, and the pleistocene valleys of the North Sea, St. George’s Channel, the British, and Irish Channels had been depressed beneath the waves of the sea before any prehistoric strata yet known had been deposited. The evidence that these changes actually took place must be referred to the two following chapters.

Comparison of Deposits in Valleys with those in Caves.

If these valley deposits be compared with the contents of some of the bone caves, such, for example, as those of the Victoria Cave (compare Figs. 74 and 75 with Figs. 20, 21, 29), it will be seen that they present the same section. The pleistocene gravels and brick-earths of the one correspond with the lower strata of the other, and contain the same extinct animals. The prehistoric alluvium of the one is represented by the layer containing neolithic bronze or iron implements, as well as the same animals; while the historic strata are represented in both by the superficial accumulations. The only difference indeed between the one and the other is, that in the former the strata of the three periods are spread over a wide area, while in the latter they are super-imposed in vertical order, the pleistocene below, the prehistoric in the middle, and the historic on the surface.

273

Difference in Mineral Condition of Deposits in Caves.

The prehistoric, and the historic strata in caves differ from the pleistocene in their physical constitution. They are darker in colour, and more loosely stratified, and contain bones in a more friable and less mineralized condition, and are more free from stalagmite.

The Caves of Germany: Gailenreuth.

The use of fossil bones for medicinal purposes led, as I have already mentioned in the first chapter, to the exploration of caves, which were first scientifically examined in Germany towards the close of the eighteenth century. They abound in all the limestone plateaux, especially in the region of Franconia, and in that of the Hartz. Among them the most interesting, perhaps, is that of Gailenreuth, explored by Esper, Rosenmüller, Goldfuss, Buckland, Lord Enniskillen, and Sir Philip Egerton. It penetrates a lofty cliff, that forms a side of the deep gorge which the river Weissent has cut in the rock, at a point about three hundred feet above the water level.

The entrance, Dr. Buckland177 writes, is about seven feet high and twelve feet broad, and within it a short passage leads into two chambers (Fig. 76, A and B),178 hung with stalactites, and with the floors covered by a dense stalagmitic pavement, that has been more or less broken up by repeated diggings. These floors are perfectly274 horizontal, the level of that of B being considerably below that of A. They rest on an accumulation of reddish grey loam, containing pebbles, and angular limestone blocks, and vast quantities of the bones and teeth of the animals formerly living in the district. The depth of this ossiferous deposit has not been ascertained, but in the further end of the chamber B, it has been proved to be more than twenty-five feet thick.

Fig. 76.—Section of Gailenreuth Cave. (Buckland.)

The remains of the animals lie scattered in the wildest confusion; sometimes being completely matted together, but more generally each bone is enveloped in earth. They belong to the lion, the cave variety of the spotted hy?na, the cave-bear, grizzly bear, mammoth, Irish elk, and reindeer, as well as to those species which are still275 to be found in Germany, such as the glutton, brown bear, wolf, fox, and stag.

It is very difficult to account for such an accumulation as this, but it was probably introduced through the present entrance, and thence into the chamber B, passing from the higher to the lower levels. The teeth-marks on the bones show that some of the animals had formed the prey of the hy?nas, but had they introduced all the bones there would have been distinct strata marking the floors of occupation, as in Wookey Hole (Fig. 88). Moreover, no perfect skulls, such as those of the bears, would have escaped their powerful teeth. The pebbles in the loam bear testimony to the passage of a current of water. And if we suppose that the cave was subject to floods, such as those in the water-caves described in the second chapter, the scattering of the bones through the loam may be explained. This, however, could not have happened had the cave then opened on the face of a nearly vertical cliff, and the only condition under which it would have been possible is, that the present entrance should have been directly connected with a stream flowing from the surface, that is to say, over the space now occupied by the gorge of the Weissent. If this view, advanced by Dr. Buckland, be accepted, the remoteness of the date of the filling up of the cave may be measured by the fact, that since that time the gorge has been cut down by the Weissent to a depth of more than 300 feet.

The stream by which the contents of the cave were introduced had a course probably analogous to that of Dalebeck (Fig. 6) and the remains of the animals were caught up from the surface, and accumulated in the276 subterranean chambers which it traversed. Their abundance offers no obstacle to this view, since wild animals frequent their drinking places in vast numbers, and fall a prey to the carnivora which lurk near the streams, and very many tumble into the natural pitfalls, or swallow-holes, so universal in limestone districts.

The Cave of Kühloch.

Very many other caves occur in the neighbourhood, most of them, such as those of Zahnloch, celebrated for the abundance of fossil teeth, Mokas, Rabenstein, and others, of which the cave of Kühloch alone demands notice.

The cave of Kühloch is situated opposite to the castle of Rabenstein, in the gorge of the Esbach, at about thirty feet from the bottom. Its exterior presents a lofty arch in a nearly perpendicular cliff, about thirty feet wide and twenty feet high, and the entrance gradually leads into two large chambers “both of which terminate in a close round end, or cul-de-sac, at the distance of about 100 feet from the entrance. It is intersected by no fissures, and has no lateral communications connecting it with any other caverns, except one small hole close to its mouth, and which opens also to the valley.” The first thirty feet present a steep slope towards the entrance. Dr. Buckland describes the contents of the chambers in the following words:179—

“It is literally true that in this single cavern (the size and proportions of which are nearly equal to those of the interior of a large church) there are hundreds of cart-loads of black animal dust entirely covering the277 whole floor, to a depth which must average at least six feet, and which, if we multiply this depth by the length and breadth of the cavern, will be found to exceed 5,000 cubic feet. The whole of this mass has been again and again dug over in search of teeth and bones, which it still contains abundantly, though in broken fragments. The state of these is very different from that of the bones we find in any of the other caverns, being of a black, or, more properly speaking, dark umber colour throughout, like the bones of mummies, and many of them readily crumbling under the finger into a soft dark powder resembling mummy powder, and being of the same nature with the black earth in which they are embedded. The quantity of animal matter accumulated on this floor is the most surprising, and the only thing of the kind I ever witnessed; and many hundred—I may say thousand—individuals must have contributed their remains to make up this appalling mass of the dust of death. It seems in great part to be derived from comminuted and pulverized bone; for the fleshy parts of animal bodies produce by their decomposition so small a quantity of permanent earthy residuum, that we must seek for the origin of this mass principally in decayed bones. The cave is so dry, that the black earth lies in the state of loose powder, and rises in dust under the feet; it also retains so large a proportion of its original animal matter that it is occasionally used by the peasants as an enriching manure for the adjacent meadows. I have stated that the total quantity of animal matter that lies within this cavern cannot be computed at less than 5,000 cubic feet; now allowing two cubic feet of dust and bones for each individual animal, we shall have in this single vault the remains of at least 2,500 bears, a number278 which may have been supplied in the space of 1,000 years by a mortality at the rate of two and a half per annum.”

Dr. Buckland’s explanation, that the cave was inhabited by bears for long generations, is probably true. The absence of pebbles and silt show that water had no share in the introduction of the remains; their preservation is due to the dryness of the cave, and to its proximity to the outer atmosphere.

The famous caves of Sundwig, Schartsfeld, and Bauman’s Hole, belong to the same class as Gailenreuth, and offer no differences which need be described.

These explorations establish the fact that, in the antediluvian age which we now term pleistocene, the lion, the cave-bear and grizzly bear, and cave-hy?na abounded in Germany, and that they sought as their prey not merely the wild animals now living in that region, but the reindeer, mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and Irish elk. All the discoveries in the German caves from the date of the exploration of Gailenreuth have merely verified this conclusion without adding any new fact of importance.

The Caves of Great Britain.

These discoveries in the German caves led to the exploration of those in our country. Dr. Buckland visited Gailenreuth in 1816, and in 1821 applied the result of his knowledge gained in Germany to the investigation of the famous cavern of Kirkdale.279180

The Hy?na-den at Kirkdale.

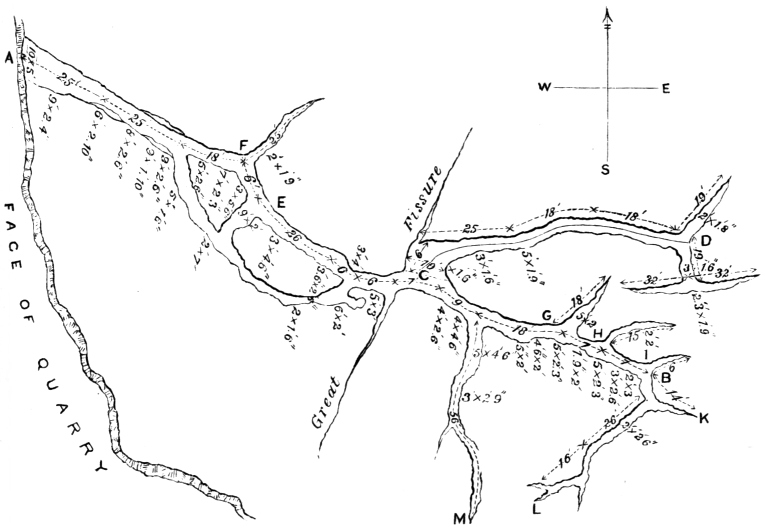

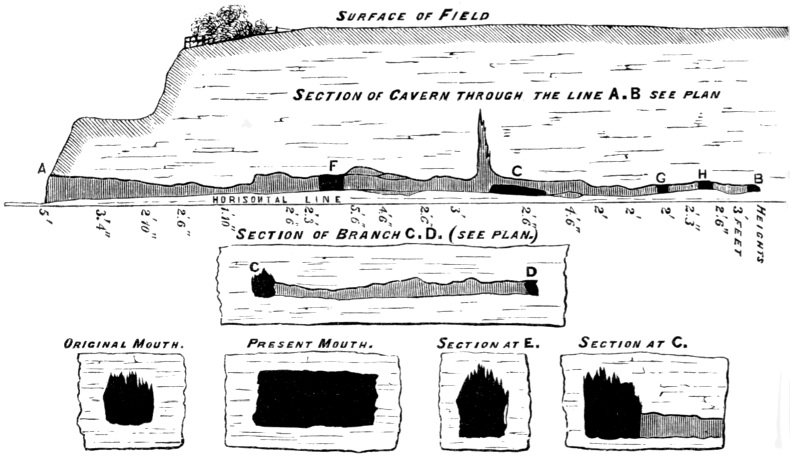

Fig. 77.—Plan of Kirkdale Cave. (Taylor.)

The cave of Kirkdale (Figs. 77, 78) was discovered in a quarry in the vale of Pickering, about twenty-five miles to the NN.E. of York, at a point where the dale of Holmbeck joins Kirkdale. The entrance, eighty feet above the valley bottom and twenty feet from the surface of the plateau above, was about three feet high and six feet wide, and led into a passage from five to ten feet wide, which ran nearly horizontally into the rock, and branched off into smaller ramifications. Its general form and size may be gathered from the examination of the accompanying woodcuts, which were published by Mr. Taylor in “Macmillan’s Magazine,” in September 1862. The roof was for the most part free from stalactite, and there was no continuous coating of stalagmite on the280 floor, but merely here and there a few calcareous bosses termed “cows’ paps” by the workmen.

Fig. 78.—Sections of Kirkdale Cave. (Taylor.)

A layer of fine red loam covered the bottom, in the lower portions of which were large numbers of gnawed and broken bones, and teeth, for the most part of the same species as those formed in the German caves. In some places they were lying in little confused heaps, and in others, where the loam was thin, were exposed to the calcareous drip and cemented into a mass, their upper portions projecting through the stalagmite “like the legs of pigeons through pie-crust,” and their irregular distribution resembling that of the fragments scattered on the floor of a dog-kennel.

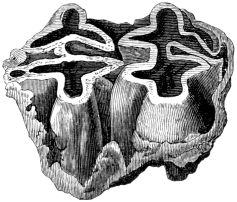

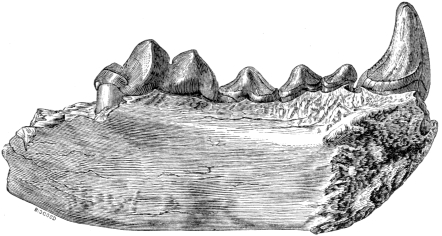

The remains of the animals were incredibly abundant, when the small space in which they were packed was taken into consideration. Those of the hy?na are estimated by Dr. Buckland as belonging to between two or three hundred individuals of all ages. The lion and the281 cave-bear, the wild boar, the hippopotamus (Fig. 79) an extinct kind of elephant (E. antiquus), and the rhinoceros named by Dr. Falconer R. hemit?chus, the reindeer, and Irish elk are also represented, but the species of most common occurrence are the bison and the horse. With a few exceptions all the bones with marrow were broken, and scarred by teeth, while the solid and marrowless were more or less perfect.

Fig. 79.—Molar of Hippopotamus. (Buckland.)

Dr. Buckland’s method of solving the problem of the introduction of remains of so many and different animals into so small a space, is a model of scientific analysis. He argues from the abundance of the remains of the hy?na, and from the correspondence of their teeth with the marks on the bones, and from the quantity of their coprolites, that the cave was inhabited by many generations of those animals, and that the gnawed fragments were relics of their prey. The hy?nas of the present day inhabit caves strewn with the bones of their prey, which are crushed by their powerful jaws into the same form as those of Kirkdale. He further demonstrated the truth of his conclusion by the crucial experiment of subjecting the leg-bone of an ox to a spotted hy?na from the Cape of Good Hope, in Wombwell’s Menagerie. “I was able,” he writes,181 “to observe the animal’s mode of proceeding in the destruction of bones: the shin-bone of an ox being presented to this hy?na, he began to bite off with his molar teeth large282 fragments from its upper extremity, and swallowed them whole as fast as they were broken off. On his reaching the medullary cavity, the bone split into angular fragments, many of which he caught up greedily and swallowed entire: he went on cracking it till he had extracted all the marrow, licking out the lowest portion of it with his tongue: this done, he left untouched the lower condyle, which contains no marrow, and is very hard. The state and form of this residuary fragment are precisely like those of similar bones at Kirkdale; the marks of teeth on it are very few, as the bone usually gave off a splinter before the large conical teeth had forced a hole through it; these few, however, entirely283 resemble the impressions we find on the bones at Kirkdale; the small splinters also in form and size, and manner of fracture, are not distinguishable from the fossil ones. I preserve all the fragments and the gnawed portions of this bone, for the sake of comparison by the side of those I have from the antediluvian den in Yorkshire: there is absolutely no difference between them, except in point of age. The animal left untouched the solid bones of the tarsus and carpus, and such parts of the cylindrical bones as we find untouched at Kirkdale, and devoured only the parts analogous to those which are there deficient. The keeper, pursuing this experiment to its final result, presented me the next morning with a large quantity of album gr?cum, disposed in balls, that agree entirely in size, shape, and substance with those that were found in the den at Kirkdale. The power of his jaws far exceeded any animal force of the kind I ever saw exerted, and reminded me of nothing so much as of a miner’s crushing mill, or the scissors with which they cut off bars of iron and copper in the metal foundries.”

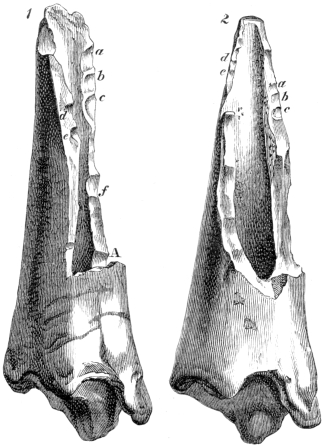

Fig. 80.—Leg-bones gnawed by Hy?nas—1, of Ox in Menagerie; 2, of Bison in Kirkdale. (Buckland.)

The exact correspondence of one of the fragments of the tibia of an ox, gnawed by the Cape hy?na, with the corresponding bone of the bison from Kirkdale, may be gathered from a comparison of the two figured in Fig. 80, in which the teeth-marks a, b, and c, are very distinct. The same kind of identity runs through the whole series of bones gnawed by the living and fossil hy?nas.

Dr. Buckland’s conclusion, that the Kirkdale cave was the den of the spotted hy?nas (H. crouta) that preyed upon the animals of Yorkshire in ancient times, and that it was undisturbed down to the time of its exploration,284 cannot be disputed. The tread of the hy?nas in their passage to and fro had polished some of the bones and jaws scattered on the floor, and the polished surfaces were uppermost, the rest of the fragments being rough. And Prof. Phillips informs me that the leg-bone of a ruminant was discovered wedged into a small fissure in the floor, with that portion which was within reach of the hy?na’s teeth gnawed away, while the rest was uninjured. The hy?na had lost his bone in the fissure, and was only able to nibble the end which projected. In these incidents we have a vivid picture of an hy?na’s den in Yorkshire during the pleistocene age, with the contents left in their natural order and not rearranged by the passage of water.

The Victoria cave near Settle, in Yorkshire, described in the third chapter, has also been occupied by hy?nas.

Caves of Derbyshire: the Dream-cave near Wirksworth.

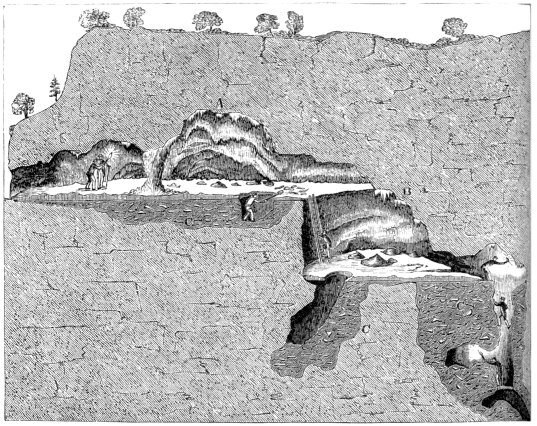

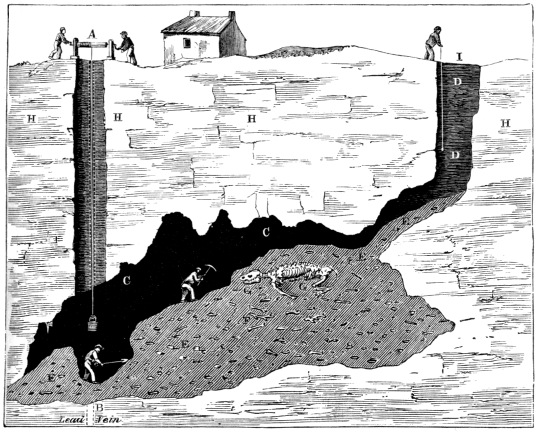

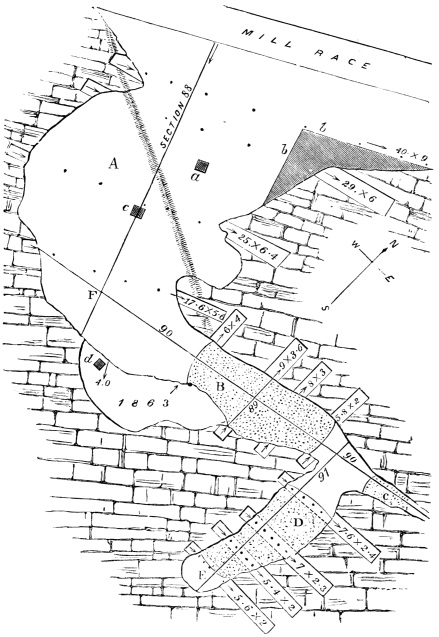

The Dream-cave, near Wirksworth,182 in Derbyshire, contrasts with that of Kirkdale in the perfect state of the bones which it contains. It was discovered in 1822, in following a vein of lead (Fig. 81). The miners suddenly broke into a hollow, c, filled with red earth and stones, and as they continued their shaft downwards the sides continually closed upon them until the roof of a cave was revealed. A nearly perfect skeleton of the rhinoceros was discovered in the earth, as well as bones of the horse, reindeer, and urus. After a large quantity of the earth had been removed, the surface soil, i, at a little distance began to sink, and ultimately a vertical shaft285 was found to connect the cave with the surface. Into this the animals had fallen, just as at the present time sheep and oxen frequently perish in similar natural pitfalls in the limestone strata.

Fig. 81.—The Dream-cave, Wirksworth. (Buckland.)

A Shaft following lead-vein.

B Supposed continuation of lead-vein.

C Cave.

D Swallow-hole.

E Ossiferous loam.

F Antler of deer.

G Rhinoceros.

H Limestone.

I Natural entrance.

Other caves and fissures in Derbyshire have yielded remains of the extinct animals: those of Balleye, near Wirksworth, and of Doveholes, near Chaple-en-le-Frith, the mammoth, and a small cave in Hartle Dale, near Castleton, explored by Mr. Pennington and myself in 1872, the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros.

286

The Caves of North Wales, near St. Asaph.

The ossiferous caves and fissures at Cefn, near St. Asaph, in the mountain limestone that forms the south side of the Vale of Clwyd, were first described in 1833,183 by the Rev. Edward Stanley, afterwards Bishop of Norwich, who explored that which Mr. E. Lloyd had discovered about half-way down the vertical cliff, in the grounds of Cefn Hall. It consists of a narrow passage, turning on itself, and communicating with the surface of the cliff by two entrances, which were completely blocked up with red silt, containing a vast quantity of bones in very bad preservation. The bottom has not yet been reached. In one portion I found, in 1872, a deposit of comminuted bone with scarcely any mixture of loam, that rose in clouds of dust as it was disturbed. The animals belonged to the same class as those of Germany, the cave-bear, spotted hy?na, and reindeer, as well as the hippopotamus, Elephas antiquus and Rhinoceros hemit?chus of the Kirkdale cave. Pebbles derived from the boulder clay, and rounded waterworn fragments of bone, showed that the contents had been introduced into this cave by a stream. Some of the remains, which were marked with teeth, may have been introduced by the hy?nas. The flint-flakes found with the human skull and cut antlers of stag, already referred to in the fifth chapter, were discovered in the lower entrance.

The same group of animals has been obtained by Mrs. Williams Wynn, the Rev. D. R. Thomas, and myself out of a horizontal cave at the head of the defile leading287 down from Cefn to Pont Newydd, in which the remains are embedded in a stiff clay, consisting of rearranged boulder clay, and are in the condition of waterworn pebbles. From it I have identified the brown, grizzly, and cave-bear. A further examination by the Rev. D. R. Thomas, and Prof. Hughes, has recently resulted in the discovery of rude implements of felstone, and a tooth which has been identified by Prof. Busk as a human molar of unusual size.184

Fig. 82.—Left Lower Jaw of Glutton, Plas Heaton Cave.

A third cave in the neighbourhood at Plas Heaton, explored in 1870 by Mr. Heaton and Prof. Hughes, furnished the remains of the cave-bear, spotted hy?na, bison, and reindeer, and a remarkably fine specimen of the lower jaw of a glutton (Fig. 82), which I have described in the “Geological Journal” (vol. xxvii. p. 406). In a fourth cave, at Gallfaenan, the bear and reindeer were discovered. It is evident from the presence of numerous bones gnawed by hy?nas in these caves, that the valleys of the Clwyd and the Elwy were the favourite haunts of that animal in the pleistocene age.

288

Caves of South Wales in the counties of Glamorgan and Caermarthen.

The earliest cavern explored in South Wales is that of Crawley Rocks,185 Oxwich Bay, about twelve miles from Swansea. It was discovered in quarrying the mountain limestone in 1792, and contained the remains of the elephant, rhinoceros, ox, stag, and hy?na. It was completely destroyed before Dr. Buckland identified these animals in the collection of Miss Talbot of Penrice Castle.186

The line of cliffs, bounding the rocky peninsula of Gower, contains the cave of Paviland, described in the seventh chapter (p. 232), as well as the group explored by Colonel Wood of Start Hall, from the year 1848187 to the present time, Bacon Hole, Minchin Hole, Bosco’s Den, Devil’s Hole, Crow Hole, Raven’s Cliff, Spritsail Tor, and Long Hole, which are described by the late Dr. Falconer. The Rhinoceros hemit?chus was met with in comparative abundance, and in association with the woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, and E. antiquus. In Bosco’s Den there were no less than 750 shed antlers of reindeer; and in Long Hole, many flint-flakes were discovered in 1860 underneath the stalagmite, and in association with the extinct mammalia, which prove, as Dr. Falconer points out, that man inhabited that district in the pleistocene age.

These caves and fissures were at all levels in the cliff, and in some the bottoms were covered with a stratum of marine sand with sea shells, which showed that they had been washed by the sea before they had been filled by the ossiferous débris. Most of them had probably289 been filled by streams in the same manner as Gailenreuth and Wirksworth. They abound on the coast merely because a clear section has been worn by the waves. A straight cut through the rocks in any part of the district would probably show them to occur in equal abundance inland.

Caves in Pembrokeshire.

The patches of limestone on the opposite side of Caermarthen Bay, in the neighbourhood of Tenby, also contain ossiferous caverns. The Rev. G. N. Smith,188 of Gumfriston, has made a fine collection of bones and teeth of mammoth and hy?na, from a fissure in the Blackrock Quarry, close to Tenby, from a fissure in the cliff on Caldy Island, and from the Coygan cave in an outlier of limestone, near Pendine, and has discovered flakes of flint and of a peculiar hornstone in the “tunnel cave” termed the Hoyle, underneath stalagmite, in a stratum containing bones of the bear and reindeer. With the exception of the fissure in the Blackrock Quarry none of these have been fully explored. On a visit to Tenby, in 1872, I obtained many flint flakes, and bones broken by man, from the breccia in the Hoyle; and from a fissure on Caldy Island, numerous bones and teeth of young wolves, which represented a whole litter, and two metatarsals of bison, cemented together into a compact mass.

The discovery of mammoth, rhinoceros, horse, Irish elk, bison, wolf, lion, and bear, on so small an island as Caldy, indicates that a considerable change has taken290 place in the relation of the land to the sea in that district since those animals were alive. It would have been impossible for so many and so large animals to have obtained food on so small an island. It may therefore be reasonably concluded that, when they perished in the fissures, Caldy was not an island, but a precipitous hill, overlooking the broad valley now covered by the waters of the Bristol Channel, but then affording abundant pasture. The same inference may also be drawn from the vast numbers of animals found in the Gower caves, which could not have been supported by the scant herbage of the limestone hills of that district. We must, therefore, picture to ourselves a fertile plain occupying the whole of the Bristol Channel, and supporting herds of reindeer, horses, and bisons, many elephants and rhinoceroses, and now and then being traversed by a stray hippopotamus, which would afford abundant prey to the lions, bears, and hy?nas inhabiting all the accessible caves, as well as to their great enemy and destroyer man. We shall see in the ninth chapter that the elevation of the whole district above its present level is part of the general elevation of north-western Europe, and no mere small or local phenomenon.

Cave in Monmouthshire.

King Arthur’s cave,189 on the side of a beautifully wooded knoll, overlooking the valley of the Wye, near Whitchurch, in Monmouthshire, explored by the Rev. W. S. Symonds in 1871, is a hy?na den, like that of Kirkdale, containing the gnawed remains of the lion,291 Irish elk, mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and reindeer. Flint flakes, however, occurred in the undisturbed strata, which prove that it was also the resort of man. Mr. Symonds believes that the sand and gravel inside were deposited by the Wye, at a time when it flowed 300 feet above its present course, or before the valley was cut down to that depth. If this conclusion be true, the date of the occupation must be separated from the present day by a vast interval, which is only to be measured by the subsequent erosion of the valley by the slow operation of the subaerial agents, running water, ice, snow, and carbonic acid.

The only remains of the mammoth which I have examined belong to young individuals, and consist of the second and third milk-molars, a fact which I have very generally observed in hy?nas’ dens. The older mammoths would not fall an easy prey to so cowardly an animal. The cave had also been inhabited by man after the pleistocene age, for coarse pottery of the neolithic kind, and flint flakes, were dug out of an upper stratum, while I was watching the excavation, in company with the Rev. W. S. Symonds, and the “Wanderers” field club.

Caves of Gloucestershire and Somersetshire.

The outliers of mountain limestone, on the southern side of the Bristol Channel, have long been known for their ossiferous caverns and fissures. From a fissure in Durdham Down,190 near Bristol, Mr. J. S. Miller obtained fragments of bones, about the year 1820, and among them Dr. Buckland notices the fossil joint of the hind-leg of a horse, the astragalus being held in natural position,292 between the tibia and the calcaneum, by stalagmite. Subsequently a large series of animals of the same species as those of Gower were discovered in it by Mr. Stutchbury, and are preserved in the Bristol Museum.

Caves of the Mendip Hills.

The caves of the Mendip Hills were known to contain bones as early as the middle of the eighteenth century, when that of Hutton,191 near Weston-super-Mare, was discovered in working the ochre and calamine which fills some of the fissures. The miners having opened an ochre pit, south of the little village of Hutton, discovered a fissure in the limestone full of good ochre, which they followed to a depth of eight yards, until it led into a cavern, the floor of which was formed of ochre, with large quantities of white bones on the surface, and scattered through its mass. Dr. Calcott describes the bones as projecting from the sides, roof, and floor of the excavation in such quantities as to resemble the contents of a charnel-house. Subsequently it was fully explored by the Rev. D. Williams, and Mr. Beard, of Banwell.

We owe the exploration of the neighbouring caves of Banwell, Sandford Hill, Bleadon, Goat’s Hole, in Burrington Combe, and Uphill,192 to the joint labours of the two above-mentioned gentlemen, extending over the period which elapsed between 1821 and 1860. The vast quantity of remains which they obtained can only be realized by a visit to the Museum of the Somerset Arch?ological and Natural History Society, at Taunton.293193 They belong to the same species as those already mentioned from the caves of South Wales. The fauna of the Mendip is, however, characterized by the great number of lions, and by a few fragments of the glutton. Of the former animal, Mr. Ayshford Sanford and myself have met with sufficient remains to figure nearly every portion of the skeleton, and the skulls prove that it was not a tiger, as it is considered to be by some naturalists, but a true lion, differing in no respect, except in its large size, from those now living in Asia and Africa.

All these caverns consist of chambers at various levels more or less connected with fissures, and, from the perfect condition of the bones they must have been inaccessible to the bone-destroying hy?na. Their contents were introduced, as is suggested by Dr. Buckland, from the surface by streams falling into swallow-holes (see Fig. 81), which have now, under the changed physical conditions, ceased to flow.

The extraordinary quantity of remains preserved in one cave may be, to some extent, verified by a visit to that at Banwell. It consists of two large chambers, the upper one filled with thousands of bones of bison, horse, and reindeer, taken out of the red silt which originally filled it to the roof; the lower one full of the undisturbed contents, from which the bones project in the wildest confusion. This accumulation has been introduced by water, through a vertical fissure which opened on the surface. It is evident, from the very nearly perfect skulls of wolf and bear which were discovered, that the cave was not used as a den by the hy?nas. They are, however, proved to have been living close by at the time, since their skulls, and the gnawed antlers of reindeer, have been discovered294 inside. They were probably swept in by the stream along with the other bones.

The Uphill Cave.

The Cave of Uphill,194 discovered in 1826, by some workmen, and explored by the Rev. D. Williams, merits especial notice, from the peculiar conditions under which the remains of the extinct animals occurred. Like the other caves of the Mendips, it consists of fissures opening into chambers. In the upper part of one of these fissures were the remains of rhinoceros, hy?na, bear, horse, bison, and wild boar, imbedded in loam which rested on two large masses of limestone that had fallen so as to block up the fissure. Below this were no remains of the extinct animals, and the fissure ultimately led into a cave opening upon the line of cliffs. This latter had been inhabited within historic times, since many bones of sheep, or goat, and pieces of pottery, were met with, as well as a coin of the Emperor Julian. In this case, owing to the extraordinary accident of the fissure being blocked up by a fall of stone, the pleistocene accumulation is vertically above the historic; and had the barrier given way, Mr. Williams would undoubtedly have discovered the remains of the extinct mammalia, lying in a heap above the comparatively modern historic stratum. It seems to me very probable that some such accident may have caused the occurrence of the pleiocene machairodus in the Kent’s Hole cavern, in association with the pleistocene mammalia. In the long lapse of ages between the pleistocene and the present day, such accidents would be likely to occur in some295 few caverns, and we might expect to find remains of widely different ages, in certain exceptional cases, lying side by side, or even the older resting vertically over the newer. At all events we must conclude, that superposition, or association, cannot be rigidly enforced as tests of relative age in all ossiferous caverns.

The Hy?na-den of Wookey Hole.

The Hy?na-den of Wookey Hole,195 near Wells, on the south side of the Mendips, which I explored with the Rev. J. Williamson in 1859, and in the following years with Messrs. Willett, Parker, and Ayshford Sanford, is worthy of a more detailed notice, because it was among the first caverns in this country in which works of art were found under conditions that proved the co-existence of man with the extinct mammalia.

The ravine in which it was discovered, in 1852, is one of the many which pierce the dolomitic conglomerate, or petrified sea-beach, of the Triassic age, resting at the foot of the cliffs from which it was torn by the waves, and overlying the lower slopes of the Mendips (see Fig. 1). Open to the south, it runs almost horizontally into the mountain-side, until closed abruptly northwards by a perpendicular wall of rock, 200 feet or more in height, ivy-covered, and affording a dwelling-place to innumerable jackdaws. Out of a cave at its base, in which Dr. Buckland discovered pottery and human teeth, flows the river Axe, in a canal cut in the rock. In cutting this passage, that the water might be conveyed to a large paper-mill close by, the mouth of the hy?na-296den was intersected in 1852, and from that time up to December 1859 it was undisturbed save by rabbits and badgers, and even they did not penetrate far into the interior, or make deep burrows. Close to the mouth of the cave the workmen (employed in making this canal) found more than 300 Roman coins, among which were those of Allectus and of Commodus. When the Rev. J. Williamson and myself began our exploration, about twelve feet of the entrance of the cave had been cut away, and large quantities of the earth, stones, and animal remains had been used in the formation of an embankment for the stream which runs past the present entrance of the cave.

According to the testimony of the workmen, the bones and teeth formed a layer about twelve inches in thickness, which rested immediately upon the conglomerate-floor, while they were comparatively scarce in the overlying mass of stones and red earth. The workmen state also that at the time of the discovery of the cave the hillside presented no concavity to mark its presence. So completely was the cave filled with débris up to the very roof, that we were compelled to cut our way into it. Of the stones scattered irregularly through the matrix of red earth, some were angular, others water-worn; all are derived from the decomposition of the dolomitic conglomerate in which the cave is hollowed. Near the entrance, and at a depth of five feet from the roof, were three layers of peroxide of manganese, full of bony splinters, and, passing obliquely up towards the southern side of the cave and over a ledge of rock that rises abruptly from the floor: further inwards they became interblended one with another, and at a distance of fifteen feet from the entrance were barely visible. In297 and between these the animal remains were found in the greatest abundance.

Fig. 83.—Plan of Hy?na-den at Wookey Hole.

Right lines = sections; dotted areas = bone-beds; shaded areas = ashes and implements.

While cutting our way inwards (Figs. 83 and 88), we found an angular piece of flint, which had evidently been chipped by human agency, and a water-worn fragment of a belemnite, which probably had been derived from298 the neighbouring marlstone rocks. Bones and teeth of the woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, stag, Irish elk, mammoth, hy?na, cave-bear, lion, wolf, fox, and horse rewarded our labours; and frogs’ remains, cemented together by stalagmite, were abundant at the mouth. The teeth preponderated greatly over the bones, and the great bulk were those of the horse. The hy?na-teeth also were very numerous, and in all stages of growth, from the young unworn to the old tooth worn down to the very gums. Those of the mammoth had belonged to a young animal, and one had not been used at all. The hollow bones were completely smashed and splintered, and scored with tooth-marks, while the solid carpal, tarsal, and sesamoid bones were uninjured, as in the Kirkdale Cave. The organic remains were in all stages of decay, some crumbling to dust at the touch, while others were perfectly preserved and had lost very little of their gelatine.

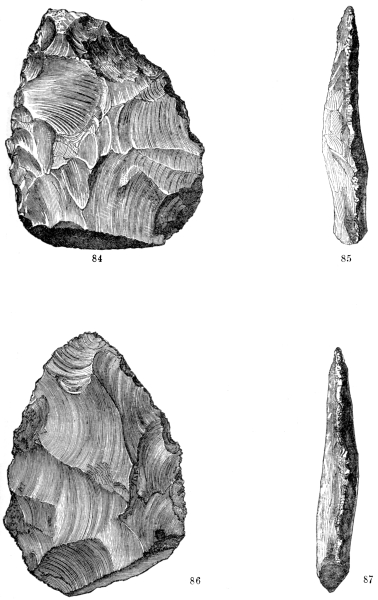

Figs. 84, 85, 86, 87.—Four Views of Flint Implements found in the Hy?na-den at Wookey Hole, near Wells.

In 1860 we resumed our excavations; and, in addition to the above remains, found satisfactory evidence of the former presence of man in the cave. Our search was rewarded by one oval implement of white flint, of rude workmanship (Figs. 84, 85, 86, 87), one chert arrow-head, a roughly-chipped and a round flattened piece of chert, together with various splinters of flint, which had apparently been knocked off in the manufacture of some implement. Two rudely-fashioned bone arrow-heads were also found, which unfortunately were subsequently lost by the photographer to whom they were sent; they resembled in shape an equilateral triangle with the angles at the base bevelled off. All were found in and around the same spot, in contact with some hy?na-teeth, between the dark bands of299 manganese, at a depth of four feet from the roof, and at a distance of twelve feet from the present entrance (Fig. 83, a).

That there might be no mistake about the accuracy of the observations, I examined every shovelful of débris as it was thrown out by the workman; while the exact spot where they were excavating was watched by my colleague. The figured implement was picked out of the undisturbed matrix by him; the rest were found by me in the earth thrown out from the same place.

The lines of peroxide of manganese must have been accumulated on the old floors of the cave, because they were associated with numerous splinters and gnawed animal remains; and there can be no doubt that the latter were introduced by the hy?nas. Those animals have a peculiar habit, as Dr. Buckland proved by experiment, of gnawing similar bones in precisely the same way; and a comparison of the relics of the meals of the hy?nas in the Zoological Gardens with those in the cave, shows that the latter have passed between the jaws of a like animal that once inhabited Somersetshire. Cop............